Novelist and journalist Tom Wolfe believed that techniques for fiction and nonfiction should be interchangeable. In a vast career that spanned greater than 50 years, Tom Wolfe wrote fiction and nonfiction best-sellers including the seminal The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test and The Bonfire of the Vanities. Along the way, he created a new type of journalism and coined phrases that immediately became part of the American English lexicon. Wolfe died Monday in Manhattan in a Manhattan hospital. He was 88. His death was confirmed by his agent, Lynn Nesbit, who said Mr. Wolfe had been hospitalized with an infection. He had lived in New York since joining The New York Herald Tribune as a reporter in 1962.

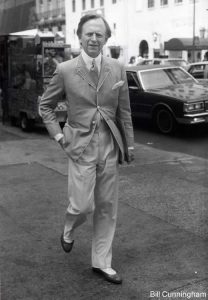

Wolfe unique philosophy on writing didn’t start a novel with a character or a plot, but rather, with an idea. Tom Wolfe loved American culture for all its excess. Groupies, doormen, hippies, astronauts, bankers and frat boys took on a magisterial presence in his writing, and if there was a hint of hypocrisy in their actions, then all the better. Wolfe revealed in worlds where people stood tall and acted with extravagance and swagger. He often joined the parade himself in his author/celebrity role, a tall, slender, blue-eyed younger looking man wearing his omnipresent cream-colored suit, pinstriped silk shirt, bright handkerchief and perfectly matching white shoes with his walking stick in hand. Tom Wolfe was an innovative, inventive journalist and novelist whose vivid and fastidiously punctuated prose brought to life the worlds of car customizers, astronauts, California surfers and Manhattan’s wealthy status-seekers in works like “The Right Stuff,” “The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby,” and his seminal “Bonfire of the Vanities.” “The Bonfire of the Vanities” is the tale of Sherman McCoy, a wealthy bond trader who winds up losing everything after a wrong turn in the South Bronx with his mistress happened to be in the passenger seat. The book was a huge critical and commercial success. Wolfe had written the novel from the same “you are there,” stream-of-consciousness, first-person perspective that he pioneered in his nonfiction 20 years earlier.

Wolfe unique philosophy on writing didn’t start a novel with a character or a plot, but rather, with an idea. Tom Wolfe loved American culture for all its excess. Groupies, doormen, hippies, astronauts, bankers and frat boys took on a magisterial presence in his writing, and if there was a hint of hypocrisy in their actions, then all the better. Wolfe revealed in worlds where people stood tall and acted with extravagance and swagger. He often joined the parade himself in his author/celebrity role, a tall, slender, blue-eyed younger looking man wearing his omnipresent cream-colored suit, pinstriped silk shirt, bright handkerchief and perfectly matching white shoes with his walking stick in hand. Tom Wolfe was an innovative, inventive journalist and novelist whose vivid and fastidiously punctuated prose brought to life the worlds of car customizers, astronauts, California surfers and Manhattan’s wealthy status-seekers in works like “The Right Stuff,” “The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby,” and his seminal “Bonfire of the Vanities.” “The Bonfire of the Vanities” is the tale of Sherman McCoy, a wealthy bond trader who winds up losing everything after a wrong turn in the South Bronx with his mistress happened to be in the passenger seat. The book was a huge critical and commercial success. Wolfe had written the novel from the same “you are there,” stream-of-consciousness, first-person perspective that he pioneered in his nonfiction 20 years earlier.

“I’ve always contended on a theoretical level that the techniques … for fiction and nonfiction are interchangeable,” he said. “The things that work in nonfiction would work in fiction, and vice versa.”

Wolfe began working as a newspaper reporter, first for The Washington Post, then the New York Herald Tribune. He developed a unique signature style, incorporating literary techniques; amped-up prose, interior monologues and eccentric punctuation. In his use of novelistic techniques in his nonfiction, Mr. Wolfe, beginning in the 1960s, helped create the enormously influential hybrid known as the “New Journalism” which he was the fervent disciple or possibly the high priest of this journalistic archetype. He brought to his stories techniques, often reserved for fiction, and he had a penchant for spotting trends within American society and then giving them checky names, some of which — like “Radical Chic” and “the Me Decade” — became permanent American idioms. The author of 15 books, fiction and nonfiction, his talent as a writer and caricaturist was evident from the start by employing meticulous reporting and a creative use of popular language and explosive punctuation.

Kurt Vonnegut considered him a genius. Mary Gordon called him a thinking man’s redneck. Surfers in La Jolla labeled him a dork after he profiled them.

As a titlist of flamboyance he is without peer in the Western world,” Joseph Epstein wrote in the The New Republic. “His prose style is normally shotgun baroque, sometimes edging over into machine-gun rococo, as in his article on Las Vegas which begins by repeating the word ‘hernia’ 57 times.”

The novelist John Gregory Dunne observed that his writings have the capacity “to drive otherwise sane and sensible people clear around the bend.”

William F. Buckley Jr., writing in National Review, put it more simply: “He is probably the most skillful writer in America — I mean by that he can do more things with words than anyone else.

Thomas Kennerly Wolfe Jr. was born in Richmond, Va., on March 2, 1931.Growing up in Richmond gave his childhood and adult persona a genteel, decidedly Southern air. His grandfather had been a rifleman for the Confederacy.

Wolfe claimed that as a child, he would thank God at night for being born in the greatest city in the greatest state in the greatest country in the world.

Wolfe’s mother was a landscape designer and encouraged him to become an artist and gave him a love of reading.

His father was an agronomist at Virginia Polytechnic Institute, as well as, an editor for an agricultural magazine, The Southern Planter and director of distribution for the Southern States Cooperative, which later became a Fortune 500 Company.

He had a sister who was five years his junior. Watching his father work, seeing scribbled notes on a legal pad transformed into pristine type on the page, sparked Wolfe’s life ambition to someday be a writer. At Washington and Lee University, he helped edit the campus

college newspaper and co-founded its literary quarterly. He played a pitcher on the baseball team and when he was 21, he unsuccessfully tried out for the New York Giants.

He received a doctorate from Yale in 1957 in American Studies and after sending out applications to 53 newspapers, took a job as a reporter for the Springfield Union in Massachusetts. The most difficult phone call he ever made, he said, was to let his father know that instead of becoming a professor, he was going to be a reporter.

He told an interviewer that he enjoyed “the cowboy nature of journalism, the idea that it wasn’t really respectable, and yet it was exciting, even in a literary way.”

After three years in Massachusetts and two years with the Washington Post, he headed to the New York Herald Tribune where he would show up each day in a $200 cream-colored suit, which he wore as “a harmless form of aggression” against New Yorkers unaccustomed to seeing lighter shades worn during winter.

Wolfe got his start writing in 1963 with a story that he almost couldn’t find the words to write. He had gone to California to report on renegade car designers working out of garages in Burbank and Lynwood. He proceeded to rack up a $750 hotel bill at the Beverly Wilshire Hotel, once he returned to New York City and stared at his typewriter, wholly unable to find the right words. As the editorial deadline approached, he typed up his notes for his editor, who at that point planned to reassign the story to another writer. Ten hours and 49 pages later, Wolfe had “The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby.”

In 1965, the story became a centerpiece for a collection of essays that established his national reputation as a writer who didn’t use the English language so much as exploits it. Allusions,

neologisms, dramatic asides, and flamboyant punctuation became the trademark of his writing style.

Surfers, sitting on the edge of the break, were like “Phrygian sacristans.”

Chuck Yeager, punching through the sound barrier above the Mojave Desert, saw the sky turn “deep purple and all at once the stars and the moon came out — and the sun shone at the same time.”

A speedboat, racing across Miami’s Biscayne Bay, slams against the waves, “throttle wide open forty-five miles an hour against the wind SMACK bouncing bouncing its shallow aluminum hull SMACK from swell SMACK to swell SMACK.”

“What Tom did with words is what French Impressionists did with color,” said Larry Dietz, editor and friend.

A disciplined writer, Wolfe held himself to a quota of 10 triple-spaced pages per day, but writing was never fun for Wolfe. “It’s the hardest work in the world,” he said. “The only thing that will get you through it is maybe someone will applaud when it’s over.”

As much as the words themselves, Wolfe’s perspective caught the attention of readers and critics. At a time when Vietnam cast a shadow across American life, he discovered something bright in stories about stock cars, Cassius Clay, Hugh Hefner and the club scene in London.

From 1965 to 1981 Mr. Wolfe produced nine nonfiction books. “The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test,” an account of his zany yet very American travels in California with Ken Kesey and his Merry Pranksters as they spread the gospel of LSD, remains a classic must-read rite of passage of the counterculture, “still the best account — fictional or non, in print or on film — of the genesis of the ’60s hipster subculture,” the media critic Jack Shafer wrote in the Columbia Journalism Review on the book’s 40th anniversary.

“Tom had an extraordinarily sharp eye and a commitment to tell the truth,” said Jann Wenner, friend and founding editor of Rolling Stone magazine. “He didn’t write out of malice. He went to the essence of the matter and called it like he saw it.”

To many critics, even more impressive was “The Right Stuff,” his exhaustively reported narrative about the first American astronauts and the Mercury space program. The book, which was adapted into a film in 1983 with a cast that included Dennis Quaid, Sam Shepard, and Ed Harris, made the test pilot Chuck Yeager a cultural hero and added yet another phrase to the English language. Subsequently, it won the National Book Award in 1980.

During this same period, Mr. Wolfe continued to turn out a stream of essays and magazine pieces for New York Magazine, Harper’s Bazaar and Esquire Magazine. His theory of literature, which he preached in print and in person and to anyone who would listen was that journalism and nonfiction had “wiped out the novel as American literature’s main event.”

Coming off the success of his ambitious and lucrative portrait of the space program, “The Right Stuff,” which was made into an Academy Award-winning movie, Wolfe turned from journalism to fiction. Having attacked contemporary novelists for their limited ambitions, he felt it only fair that he try the form himself. After “The Right Stuff,” published in 1979, he confronted what he called “the question that rebuked every writer who had made a point of experimenting with nonfiction over the preceding 10 or 15 years: Are you merely ducking the big challenge — The Novel?”

The answer came with “The Bonfire of the Vanities.” Initially, “The Bonfire of the Vanities” was written as a series in Rolling Stone magazine and finally in book form in 1987 after extensive revisions. The book offered a sweeping satirical bitingly picture of power, money, greed and vanity in New York City during the shameless excesses of the 1980s.

The prose jumps back and forth from Wall Street to Park Avenue to the terrifying holding jail cells in Bronx Criminal Court, after the Yale-educated bond trader Sherman McCoy (a self-proclaimed “Master of the Universe”) becomes lost in the Bronx at night in his Mercedes with a hot, young number who is his mistress. He proceeded to run over a black man and almost igniting a race riot, he enters the nightmare world of the criminal justice system.

The book was a runaway bestseller yet “Bonfire” divided critics into two camps: those who praised its author as a worthy heir of his fictional idols Zola, Dickens, Balzac and Dreiser, and those who dismissed the book as ‘clever journalism,’ a charge that would follow him throughout his entire fictional career.

Mr. Wolfe responded with his manifesto in Harper’s Bazaar, “Stalking the Billion-Footed Beast,” in which he crucifies American fiction for failing to perform societies duty of reporting on the facts of contemporary life, in all their complexity and variety.

His second novel, “A Man in Full” (1998) was also a whopping commercial success. Set in Atlanta, it charted the rise and fall of Charlie Croker, a 60-year-old former Georgia Tech football star turned millionaire real estate developer.

Mr. Wolfe’s fictional ambitions and commercial success earned him enemies — big ones.

“Extraordinarily good writing forces one to contemplate the uncomfortable possibility that Tom Wolfe might yet be seen as our best writer,” Norman Mailer wrote in The New York Review of Books. “How grateful one can feel then for his failures and his final inability to be great — his absence of truly large compass. There may even be an endemic inability to look into the depth of his characters with more than a consummate journalist’s eye.”

“Tom may be the hardest-working show-off the literary world has ever owned,” Mr. Mailer continued. “But now he will no longer belong to us. (If indeed he ever did!) He lives in the King Kong Kingdom of the Mega-bestsellers — he is already a Media Immortal. He has married his large talent to real money and very few can do that or allow themselves to do that.”

Mr. Mailer’s sentiments were echoed by John Updike and John Irving.

Two years later, Mr. Wolfe took revenge. In an essay titled “My Three Stooges,” included in his 2001 collection, “Hooking Up,” he wrote that his eminent critics had clearly been “shaken” by “A Man in Full” because it was an “intensely realistic novel, based upon reporting, that plunges wholeheartedly into the social reality of America today, right now,” and it signaled the new direction in late-20th- and early-21st-century literature and would soon make many prestigious artists, “such as our three old novelists, appear effete and irrelevant.”

And, he added, “It must gall them a bit that everyone — even them — is talking about me, and nobody is talking about them.” Cocky words from a man best known for his gentle manner and unfailing courtesy in person.

An inveterate New Yorker, Wolfe once said that he could imagine living nowhere else. “Pandemonium with a big grin on it,” he called Manhattan and claimed that his favorite past time was window shopping.

Single until he was 47, he met his wife, Sheila Berger, at Harper’s magazine where she was an art director and graphic designer. They married in 1978 after a long courtship and kept a two-story, 12-room townhouse on the Upper East Side and a home in Southampton, on Long Island.

She and their two children, Alexandra Wolfe, a reporter for The Wall Street Journal, and Tommy Wolfe, a sculptor and furniture designer, survive him.

Novelist and journalist Tom Wolfe believed that techniques for fiction and nonfiction should be interchangeable. “The things that work in nonfiction would work in fiction, and vice versa,” he said.

“What Tom did with words is what French Impressionists did with color.”

LARRY DIETZ, EDITOR AND FRIEND